Author: Kate Wilson, Managing Director, Impact Futures Global, LLC

Background

On October 15, the Linked Immunisation Action Network, held a webinar to share experiences amongst countries working towards developing national Electronic Immunisation Registries (EIR) and discuss strategies for making national level information systems such as national identity systems and civil registration and vital statistics systems interoperable with them.

With the goal of preventing backsliding in vaccine coverage and driving the sustainable introduction of key missing vaccines, many countries have invested in EIRs but still struggle with their implementation. In the health sector, resources such as the Pan American Health Organization in Electronic Immunisation Registries: Practical Considerations for Planning, Development, Implementation and Evaluation document how a country can connect their EIRs with health information systems. However, much less has been written about how an EIR can and should connect with national information systems which can provide essential data about citizens and ensure immunisation leaders have an accurate population denominator.

National information systems can help with common EIR challenges. For example, many countries with EIRs still grapple with making sure the system has a patient identifier for everyone in the country and not just those who have visited a clinic or managing duplicative immunisation records on the same person. Linked members struggle with patient identifier challenges which prompted this webinar to learn from countries that started with a more “top down” or national approach to leveraging population wide information systems (e.g., citizen identifiers, CRVS) to inform their health information systems and track immunisation coverage in their countries.

The discussion began with presentations from Piret Hirv, Head of the Data Management Competence Center at Estonia’s eGovernance Academy and Dr. Boonchai Kijsanayotin, Lecturer at Prince Mahidol University, Thailand who each shared how their country leveraged their national digital public infrastructure (e.g., national identity) and national data privacy policies to track immunisation coverage. In both countries, existing national identity and CRVS systems which respectively track every citizen and their status, are used as the sole source of truth to provide citizen data to the health information systems and pre-populate patient medical records. This system design allows both ministries of health and citizens to use their national id to securely access a patient’s medical record, track their immunisation status and receive alerts when a new vaccine is required without implementing a separate EIR. Contrast this “top down” approach with the “more bottom up” approach of building separate health information systems (e.g. patient registry, Electronic Medical Record, EIR) which serve only the health sector.

Why is learning about the “top down” approach to leveraging national digital public infrastructure so important for immunisation leaders?

Is this a necessary discussion if one is already developing an EIR? The resounding answer is ‘yes’ based on feedback from Linked members who struggle to get an accurate population count, identify doses received, manage moving supplies to match population movements, and de-deduplicate records. By leveraging national identity platforms and/or a CRVS system and making them interoperable with their health information systems, a nation can accelerate efforts to address common EIR challenges cited by Linked members in surveys.

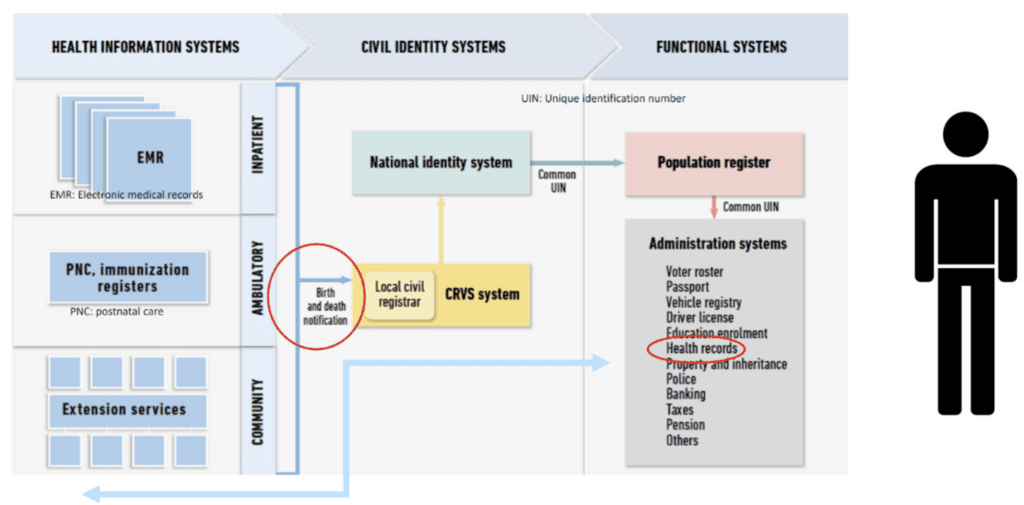

Attended by a diverse group of countries from Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America who are designing or implementing EIRS currently, the webinar started with a brief overview of the relationship between national IDs, CRVS, and EIRs and their relationship to one another as illustrated in the figure below.

Source: WHO/UNICEF Presentation

As the graphic shows, the relationship between national identity, national civil registration, and electronic immunisation registries is dynamic and interlinked. Each of these systems plays a crucial role in improving citizen welfare, strengthening healthcare systems, and fostering national development but many countries do not have all three systems in place. Therefore, when health leaders consider developing an EIR, they should understand the status of and consider the role that current or future CRVS and national ID programs will play with the EIR and plan accordingly.

This step is crucial as more countries embrace digital public infrastructure and link government service systems (e.g., EIR) to national identity systems. National ID systems issue unique identifiers to citizens and residents, which serve as a central feature for government records and public services. Civil registration systems, on the other hand, document key life events like births, deaths, and marriages. Civil registration systems can feed national identity registries with data, creating a foundational identity record for every citizen from birth. This integration is essential for countries where birth registration is critical for establishing citizenship, legal identity, and access to services, especially in sectors like healthcare and education.

Benefits of Integration

Often linked to these systems, EIRs track vaccination history and immunisation schedules for individuals within a country. EIRs are increasingly digitized to facilitate real-time data collection, enabling healthcare providers to ensure that people, especially children, receive timely vaccinations. EIRs can benefit significantly from integration with civil registration and national identity systems by linking immunisation records to unique identifiers. This integration helps to:

- Accurately track vaccination coverage, monitor population immunity levels, and identify individuals needing follow-up.

- Reduce duplicate records and improve efficiency in healthcare systems.

- Support cross-border immunisation tracking, critical in regions with high migration.

- Improve forecasting for vaccine supply logistics systems.

Furthermore, when national identity, civil registration, and EIRs are linked, countries can leverage integrated data to provide a holistic view of a person’s health and demographic information. This linkage supports:

- Better healthcare planning and resource allocation, as authorities gain access to reliable data on population demographics and healthcare needs.

- Enhanced social services delivery, since healthcare and other services can be directly tied to individuals based on their national ID.

Improved public health interventions, as policymakers can identify immunisation gaps and target where to deploy staff more efficiently and rapidly to minimize the impact of outbreaks. When present, this triad of systems supports achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC), addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) like good health and well-being (SDG 3), and reducing inequalities (SDG 10). However, questions remain on whether all three systems are needed, in what order they should be developed, and how Linked members can make these systems interoperable and garner financial, political and legislative support for their development. So, what steps did Estonia and Thailand take to build this support and how did they approach using national DPI to inform vaccine tracking?

Insights from Estonia and Thailand

Thailand does not have a centralized EIR and instead immunisations are recorded with an individual’s patient medical record which is tied to their national identity number, and national immunisation coverage is tracked within different disease programmes at the Ministry of Health. Thailand’s national information systems approach stems from its early embrace of achieving Universal Health Coverage and ensuring the whole population has access to affordable health services. Patient medical records are interoperable with the national population register that generates a citizen ID (CID). The CID has been in place since 1982 when Thailand shifted from a paper-based civil registration system to a computerized and centralized population database created by the Ministry of Interior (MoI). The CID is issued at birth as a unique national identifier used throughout the citizens life and is shared with all functional systems administered by the government (e.g., immigration, land register). While there have been many iterations of the CID, the current version is a smartcard with a thirteen-digit unique number. This unique identifier is the primary source of information on Thailand’s citizens and is also leveraged by other functional databases (e.g., education) across the government. The system allows for integration with CRVS functions managed at the district level where all births and deaths are captured digitally and which, by law, all Thai citizens must report within 48 hours of either event.

This “top down” approach of leveraging one national identifier to provide input to sector specific systems represents one approach to pre-populating an EIR with a country’s entire population. Key to this approach is a national political commitment and consistent investment over decades in the necessary electronic systems and supporting policy frameworks to ensure data privacy, no matter what the system. As Dr Boonchai noted, a key benefit of this approach is the ability to view immunisation data from the level of population coverage-down to an individual’s vaccination status. However, Thailand has chosen not to invest in an EIR and so population level immunisation data, can be more challenging to track – a benefit of also adding an EIR.

Estonia’s system is similar to Thailand’s in that they also have chosen a “top down” approach. Piret emphasized that in general the technology is the easy part. What is often more challenging is building the political will, putting in place the legal framework, and facilitating change management across multiple ministries and within the health system. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Estonia deliberately built its electronic systems to support its societal functions, placing individual privacy and consent at the heart of its design principles.

Estonia also utilizes a unique identifier (UID) which is a physical and virtual card that is issued to all citizens and used across all sectors (e.g., healthcare, banking, education) to access government services. The UID also provides information, if a user grants permission, which feeds Estonia’s national registries and its patient portal utilized by public and providers alike. Estonia’s nationwide health information system (HIS) includes both public healthcare and private service providers and is interoperable with other national systems. Central to Estonia’s healthcare system, the HIS and the patient portal reduce the need for separate immunisation registries by disease program; immunisation follow-up is done through notifications from the health information system to the patients, and patients can follow up with doctors directly when they are requesting new vaccines. The system uses a two-step identifier: (1) validation when the patients enter their ID and (2) organization-based validation when a facility inputs data. Healthcare providers have separate access for their professional needs, and entering data into the system is mandatory. Healthcare providers accessing the system must be accredited and registered. Further, every person in Estonia has a medical record; they cannot opt out or delete their data; however, they can restrict doctor’s access to the data and see who has access to their data. Children’s data is connected to their parents’ IDs, so parents can see their children’s data until they are 18 years old.

Piret shared that despite the high coverage rate and sophistication of the system, or perhaps because of it, Estonia like many countries faces declining vaccine coverage. In 2014 vaccination coverage in Estonia was 95%; however, today it is 73-83% depending on the vaccine due to increasing vaccine hesitancy.

Conclusions

While the approaches to tracking immunisation coverage and developing EIRs is as varied as the number of countries, it is useful for countries just beginning this journey to consider if they should take a “top down” national digital public infrastructure approach in which an EIR is not essential versus a more specialized “bottoms up” approach common in many countries in which the health system and/or the expanded program on immunisation developed its EIR ahead of a national identifier. Both are common practices, and each has advantages and disadvantages. Some countries, notably Indonesia, Viet Nam and Georgia, discussed the benefits and challenges of having all three systems in place and working towards greater interoperability. Whatever approach countries choose to pursue, learning from the different approaches and experiences shared by Linked members can accelerate getting to an accurate denominator and improving equitable vaccine coverage. Learn more by listening to the full recording located here.